The Sacred and the Scored: Korea’s Hagwons and the Price of Devotion

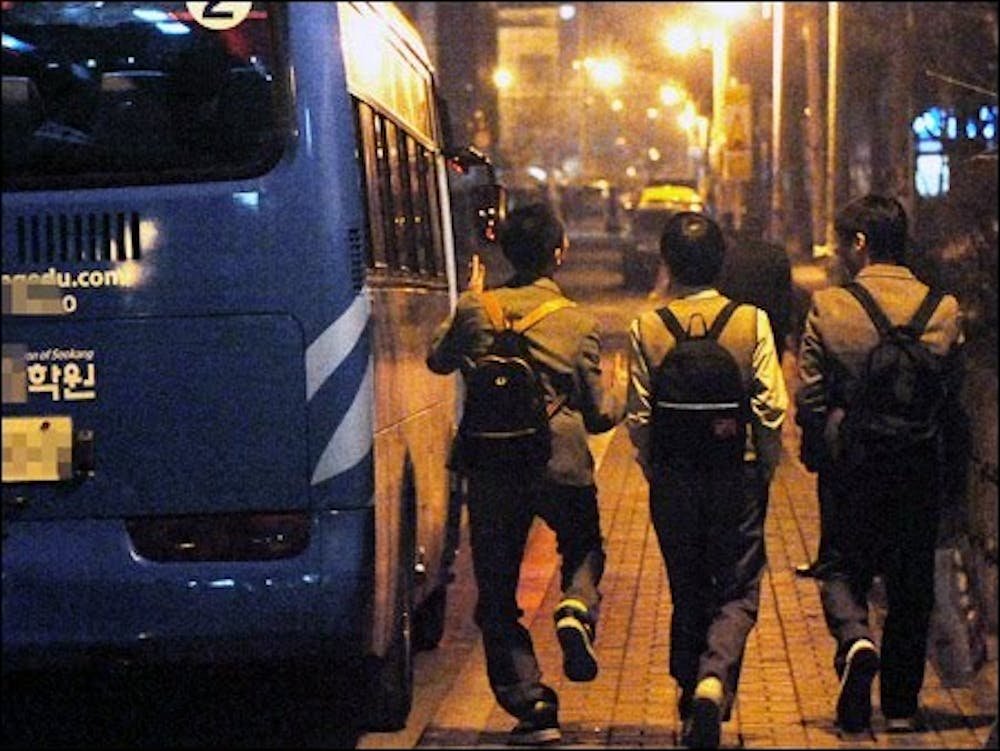

In the heart of Seoul, the lights stay on late. Beneath neon signs stacked like shelves, students file into narrow buildings carrying backpacks heavy with not only books, but also expectations of academic success. In South Korea education doesn't end when the bell rings. In the dense corridors of ‘hagwons’; private after-school academies; the work of learning continues deep into the night.

South Korea education has for a long time attracted admiration for its discipline and achievment, consistently ranking among the highest scoring education systems in terms of international assessments like PISA. Yet behind this success lies a shadow system that defines modern Korean education as much as any classroom. Hagwons are often characterised as a symptom of pressure, inequality, or excess. But to understand their power (and their persistence) we must see them not only as economic institutions but as cultural expressions. The hagwon does not simply exist because of competition. It exists because, in Korean society, learning itself carries moral weight.

From Confucian Virtue to Capitalist Efficiency

The roots of Korea's education obsession reach back centuries. During the Joseon dynasty, scholars studied for years to pass the ‘gwageo’ civil service exams. These were ritualised gateways to social prestige. Education was never just about knowledge; but was also about virtue, duty, and family honour. The ideal scholar was both learned and morally upright. To study diligently was to live ethically.

That Confucian tradition endured, mutating through war, industrialisation, and the digital age. When South Korea rebuilt after the Korean War, education became a machine of national recovery. By the 1980s a new ideology had emerged; a fusion of meritocracy and Confucian morality. Diligence became a patriotic obligation and was no longer just a matter of personal virtue. Parents poured their savings into education to secure status, as much as to express care and sacrifice. In this sense, the family that invests is the family that loves.

Hagwons, which proliferated in this era, became the modern expression of that ethic. What began as private tutoring evolved into academies driven by both moral duty and market logic. Within their walls, Confucian self-cultivation met capitalist self-optimisation; and found surprisingly a comfortable home.

Education as Love, Labour, and Status

In South Korea, the phrase education fever (kyoyuk yeol) captures a national obsession with a moral dimension. To study hard is to be virtuous; to provide for your child's learning is an act of devotion. In this moral economy, hagwons are not seen as indulgence—they are evidence of care. Not enrolling a child in a hagwon feels negligent for many parents. Education is a form of emotional labour in which economic spending is transformed into moral expression.

A poster for the K-Drama ‘The Midnight Romance in a Hagwon’ (2024). Even in fiction, the hagwon is where Korea's anxieties of sacrifice, success, and self-worth find a stage.

This ethic blurs into anxiety. Families measure themselves by the opportunities they can provide. The market exploits that anxiety: hagwons sell not only instruction but reassurance. They promise not just better scores, but peace of mind in a society where competition feels existential. Some children are sent to hagwons as young as four—years before the pressure formally begins, but long before it ends.

All of this is in service of a single event: the Suneung, South Korea's national college entrance exam. Held every November, it is an eight-hour marathon of roughly 200 questions that dictates not only university entry, but job prospects, income, and even future relationships. On the day it is administered, the country reorganises itself around it. Construction halts. During the English listening section, all flights are banned from taking off or landing — a 35-minute window in which over 140 flights across the country are rescheduled. Military training is suspended. The nation holds its breath.

The Hidden Curriculum of Pressure

The moral force of diligence, however, carries costs; and they fall hardest on the students themselves. In 2024, a survey by the Korean educational research institute found that over 60% of high school students reported sleeping fewer than five hours a night during exam season. Surveys regularly place Korean teenagers among the most anxious and depressed students in the OECD. Many describe schooling not as a path to knowledge, but as a form of endurance—something to survive rather than inhabit. One student interviewed by the Korean Broadcasting System described her routine: school until four, hagwon until eleven, homework until two. "There is no day," she said, "that belongs to me."

Hagwons reinforce this cycle. They are a parallel system that teaches implicitly that rest is weakness and that one's worth is measurable in points and rankings. The Suneung sharpens this further. In an interview with the BBC, English professor Jung Chae-kwan, who previously worked at the institution that administers the exam, argued that teachers end up drilling test-taking strategies rather than teaching the language itself. The goal is not comprehension—it is performance. Students learn to extract answers without fully reading the material, and the system rewards them for it.

Yet for all the criticism, hagwons also fill real gaps. They offer individualised attention, flexible pacing, and often better instruction than overburdened public schools. They are both symptom and solution—a mirror reflecting the strengths and contradictions of Korea's education culture.

This tension found sharp expression in the 2018 Korean drama Sky Castle, which satirised wealthy families consumed entirely by university admissions strategy. The show was not simply entertainment; it became a national conversation. Audiences recognised themselves in its depictions of parents who loved their children fiercely and, in that very love, pushed them toward breaking point. The drama's popularity suggested something uncomfortable: that most Koreans understood the system's cruelty and participated in it anyway, because opting out felt like abandoning their children to failure.

When Virtue Meets the Market

The hagwon's endurance cannot be explained by policy or profit alone. It is sustained by moral legitimacy. The act of studying—whatever its form—retains deep ethical meaning in a society built on the idea that effort is destiny. The hagwon translates that virtue into performance, devotion into data.

But this alignment between moral conviction and market logic creates a problem that regulation cannot solve. Curfews, fee caps, and bans have been tried repeatedly—and repeatedly failed. In 2006, the government imposed a 10 p.m. curfew on hagwons, backed by the Constitutional Court. It made little difference. Demand simply shifted to other forms of private tutoring. The policy targeted structure, not belief. To change the hagwon system would mean redefining what counts as good parenting, responsible citizenship, and moral worth. That is not a policy question. It is a cultural one.

Rethinking Success

To the rest of the world, South Korea's educational ascent appears enviable. It serves as a model of discipline, consistency, and excellence. Yet its shadow reveals a deeper fact that excellence pursued without rest can hollow out the very lives it seeks to elevate.

The hagwon is a mirror to Korean culture, not an aberration. It reflects a society where learning is sacred, but where the sacred has been commercialised; care has become consumption. The line between devotion and damage is not always clear, and for millions of Korean families, it may not yet be drawn.

The question is not whether Korea should have fewer hagwons. It is whether anyone—in Korea or elsewhere—can imagine an education that preserves diligence without despair. For now, no one has answered it. The lights in Gangnam stay on.

Further Reading

Anon (2015) The creme de la cram; Education in South Korea. The Economist (London) 416 (8956) p.38.